Un approccio multidisciplinare ha permesso di stimare la probabilità del ripetersi di esplosioni più intense dello Stromboli dopo che una di esse è avvenuta

(3 luglio e 28 agosto)

Roma/Bristol, 15 ottobre 2020 – Stromboli, il “faro del Mediterraneo”, è un vulcano famoso per la sua attività esplosiva di bassa energia e persistente, nota proprio col nome di attività stromboliana. Questa caratteristica è da sempre una forte attrazione per i visitatori e per i vulcanologi di tutto il mondo.

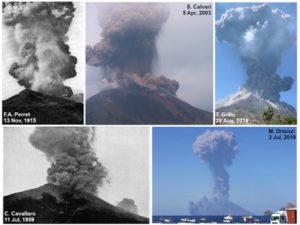

Tuttavia, occasionalmente – come recentemente avvenuto il 3 luglio e 28 agosto 2019 – si verificano esplosioni più intense ed improvvise che possono rappresentare un grave pericolo, i cosiddetti “parossismi stromboliani”. Già descritti dal geologo Giuseppe Mercalli all’inizio del secolo scorso, durante questi eventi sono coinvolti simultaneamente più crateri e vengono eruttati volumi più elevati di materiali piroclastici.

L’obiettivo dello studio “Major explosions and paroxysms at Stromboli (Italy): a new historical catalog and temporal models of occurrence with uncertainty quantification”, appena pubblicato sulla rivista ‘Scientific Reports’ di Nature, è stato stimare le frequenze di accadimento dei parossismi stromboliani e verificare se il vulcano avesse una sua “memoria”, ovvero se era possibile individuare una ricorrenza statistica tra un’eruzione parossistica e la successiva. Ha quindi cercato di rispondere alle domande “quanto sono probabili questi fenomeni esplosivi più violenti?” e “quanto diventano più probabili dopo che uno di essi è avvenuto, e per quanto tempo?”.

Per rispondere a queste domande, un team di ricercatori dell’Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) e dell’Università di Bristol (UK) ha elaborato un nuovo catalogo nel quale vengono descritti 180 eventi esplosivi violenti di varia scala accaduti a Stromboli dal 1879 al 2020. In particolare, 36 dei 180 eventi esplosivi censiti sono parossismi, analoghi a quelli dell’estate 2019.

Per questo studio, i ricercatori hanno valutato in maniera critica eventi descritti in lavori scientifici del passato e informazioni riportate in testi storici e narrativi, determinando, su basi oggettive ed omogenee, il tipo e l’intensità della attività esplosiva indipendentemente dall’enfasi dei racconti.

“Il nuovo catalogo che abbiamo messo a punto – spiega Massimo Pompilio, primo ricercatore dell’INGV e coautore dello studio – ha permesso di rivedere la classificazione di numerosi eventi attraverso l’analisi critica delle fonti storiche. Dall’analisi emerge che il tasso annuale medio dei parossismi degli ultimi 140 anni è stato di 0.26 eventi/anno, ovvero un evento ogni 4 anni circa. Questo tasso è vicino a quello calcolato negli ultimi dieci anni, ma molto inferiore a quello raggiunto negli anni ’40 del secolo scorso, quando questi eventi parossistici erano assai più frequenti. Il vulcano alterna quindi periodi di attività intensa e periodi di relativa quiete”.

“Il breve lasso di tempo di 56 giorni osservato fra i due parossismi dell’estate 2019 – continua Massimo Pompilio – non ѐ quindi una situazione rara. Per ben cinque volte negli ultimi 140 anni ci sono stati tempi inter-evento ancora più brevi. Viceversa, ci sono stati quattro periodi senza parossismi lunghi dai 9 ai 15 anni, ed un intervallo senza gli stessi che si è protratto addirittura per 44 anni, dal 1959 al 2003”.

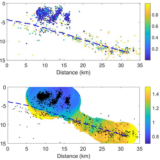

Queste informazioni sono anche utili in un contesto previsionale, ovvero per stimare le probabilità di accadimento futuro di questi fenomeni. Andrea Bevilacqua, ricercatore INGV e primo autore dello studio spiega: “Quando un fenomeno, come un’esplosione vulcanica si verifica a intervalli irregolari nel tempo, quello che si studia è la distribuzione dei ‘tempi di inter-evento, ossia dei tempi intercorsi in passato fra un’esplosione e quella successiva. In particolare lo sviluppo dei modelli di inter-evento ci permette di calcolare la probabilità di accadimento di una esplosione in funzione del tempo trascorso dall’ultimo evento di quel tipo. Una importante evidenza emersa dalla nostra ricerca riguarda la tendenza dei parossismi a verificarsi in gruppi. Sempre sulla base dei dati degli ultimi 140 anni, abbiamo stimato che esiste il 50% di probabilità che un parossisma si verifichi entro dodici mesi dal precedente e il 20% di probabilità che lo segua in meno di due mesi; d’altro canto esiste anche un 10% di probabilità che trascorrano oltre dieci anni senza che si verifichino altri parossismi”.

Una ‘memoria’ del vulcano del tutto simile, seppur con stime di accadimento diverse, emerge considerando, insieme ai parossismi, anche le cosiddette “esplosioni maggiori”, esplosioni più frequenti dei parossismi ma dotate di minor energia e pericolosità.

“Questo studio ha mostrato come, in termini di occorrenza dei fenomeni esplosivi più violenti dell’ordinario, lo Stromboli stia attraversando, negli ultimi anni, una delle fasi di attività più intense della sua storia recente – conclude Augusto Neri, Direttore del Dipartimento Vulcani dell’INGV e coautore dello studio – La stima della ‘memoria’ dell’attività esplosiva più intensa dello Stromboli potrà dare un significativo contributo alla quantificazione della pericolosità di questi fenomeni e, di conseguenza, alla riduzione del rischio associato. Inoltre, l’analisi dei dati suggerisce l’esistenza di un processo fisico che in qualche misura influenza la frequenza delle esplosioni del vulcano rendendole eventi eruttivi non completamente casuali. Capire le ragioni e i meccanismi fisici che determinano questa memoria rappresenta un’ulteriore sfida scientifica”.

La ricerca pubblicata ha una valenza essenzialmente scientifica, priva al momento di immediate implicazioni in merito agli aspetti di protezione civile.

*******

Stromboli, the ‘memory’ of the volcano measured to estimate the probability of explosive eruptions

A multidisciplinary approach made it possible to estimate the probability of further intense explosions of Stromboli when one has just occurred

Rome/Bristol, October 15, 2020 – Stromboli, the “lighthouse of the Mediterranean”, is a volcano famous for its low-energy but persistent explosive eruptions, behavior known scientifically as Strombolian activity. This feature has always been a strong attraction for visitors and volcanologists from all over the world.

However, occasionally – as recently occurred on 3rd July and 28th August 2019 – more intense and sudden explosions occur, which can represent a serious danger, the so-called “Strombolian paroxysms”. These larger eruptions were described by the geologist Giuseppe Mercalli at the beginning of the last century and, during such events, several of Stromboli’s craters are active simultaneously, with volumes of pyroclastic materials being erupted that are much greater than is “normal” for explosions from the volcano.

The aim of the study “Major explosions and paroxysms at Stromboli (Italy): a new historical catalog and temporal models of occurrence with uncertainty quantification”, just published in the journal ‘Scientific Reports’, was to estimate the frequency of occurrence of Strombolian paroxysms and to investigate if the volcano has its own ‘memory’ as evidenced, in statistical terms, by a temporal recurrence relationship between one paroxysmal eruption and the next. The study then tackled the questions: “how likely are these more violent explosive phenomena?” and “how much more likely do they become after one of them has just happened, and for how long?”.

To answer these questions, a team of researchers from the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) and the University of Bristol (UK) has developed a new catalog which describes 180 violent explosive events of varying scale that occurred at Stromboli from 1879 to 2020. In particular, 36 of these historic explosive events were of the much larger paroxysm type, similar to those of the summer of 2019.

For this study, the researchers critically evaluated events described in past scientific works and from information recorded in historical texts, determining, on an objective and homogeneous evidential basis, the type and intensity of the explosive activity – regardless of any narrative hyperbole in the written accounts.

“The new catalog that we have developed – explains Massimo Pompilio, senior researcher at INGV and co-author of the study – made it possible to review the classification of numerous events through the critical analysis of historical sources. From the analysis it emerges that the average annual rate of paroxysms of the last 140 years was 0.26 events/year, i.e. one event every 4 years or so. This rate is close to that calculated in the last ten years, but much lower than that achieved in the 40s of the last century, when these paroxysmal events were much more frequent. The volcano therefore alternates periods of intense activity and periods of relative quiet”.

“The short span of 56 days observed between the two paroxysms of summer 2019 – continues Massimo Pompilio – is therefore not a rare situation. Five times in the past 140 years there have been even shorter inter-event times. Conversely, there have been four periods without paroxysms lasting from 9 to 15 years, and an interval without paroxysms that lasted for 44 years, from 1959 to 2003”.

This information is also useful in a forecasting context, i.e. to estimate the probabilities of future occurrence of these volcanic phenomena. Andrea Bevilacqua, INGV researcher and first author of the study explains: “When a phenomenon, such as a volcanic explosion, occurs at irregular intervals in time, what is studied is the distribution of the ‘inter-event’ times, i.e. the times elapsed in passed between one explosion and the next. In particular, the development of inter-event models allows us to calculate the probability of an explosion occurring as a function of the time elapsed since the last event of that type. An important evidence that emerged from our research concerns the tendency of paroxysms to occur in groups. Still on the basis of data from the last 140 years, we have estimated that there is a 50% probability that a paroxysm will occur within twelve months of the previous one and a 20% probability that it will follow it in less than two months; on the other hand, there is also a 10% probability that more than ten years will pass without any other paroxysms occurring”.

A very similar ‘memory’ property of the volcano, though with different rates of occurrence, emerges if, together with the paroxysms, the so-called “major explosions” are also considered. The latter explosions occur more frequently than paroxysms but with less energy and less danger.

“This study showed how, in terms of the occurrence of the most violent explosive phenomena of the ordinary, Stromboli is going through, in recent years, one of the most intense phases of its recent history – concludes Augusto Neri, Director of the Volcanoes Department of the INGV and co-author of the study – The estimation of the ‘memory’ of the most intense explosive activity of Stromboli will make a significant contribution to the quantification of the danger of these phenomena and, consequently, to the reduction of the associated risk. Furthermore, the analysis of the data suggests the existence of a physical process that to some extent influences the frequency of the volcano’s explosions, making them not completely random eruptive events. Understanding the reasons and physical mechanisms that determine this memory represents a further scientific challenge”.

The published research has a scientific value with no immediate implications in terms of civil protection issues.

Link to the study: www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-74301-8

Salva come PDF

Salva come PDF